Political cartoon

{{#invoke:sidebar|sidebar | outertitle = Political cartoon

| title = Comics

A political cartoon, also known as an editorial cartoon, is a cartoon graphic with caricatures of public figures, expressing the artist's opinion. An artist who writes and draws such images is known as an editorial cartoonist. They typically combine artistic skill, hyperbole and satire in order to either question authority or draw attention to corruption, political violence and other social ills.[1][2]

Developed in England in the latter part of the 18th century, the political cartoon was pioneered by James Gillray,[3] although his and others in the flourishing English industry were sold as individual prints in print shops. Founded in 1841, the British periodical Punch appropriated the term cartoon to refer to its political cartoons, which led to the term's widespread use.[4]

History

[edit]Origins

[edit]

The pictorial satire has been credited as the precursor to the political cartoons in England: John J. Richetti, in The Cambridge history of English literature, 1660–1780, states that "English graphic satire really begins with Hogarth's Emblematical Print on the South Sea Scheme".[7][8] William Hogarth's pictures combined social criticism with sequential artistic scenes. A frequent target of his satire was the corruption of early 18th century British politics. An early satirical work was an Emblematical Print on the South Sea Scheme (c. 1721), about the disastrous stock market crash of 1720 known as the South Sea Bubble, in which many English people lost a great deal of money.[9]

His art often had a strong moralizing element to it, such as in his masterpiece of 1732–33, A Rake's Progress, engraved in 1734. It consisted of eight pictures that depicted the reckless life of Tom Rakewell, the son of a rich merchant, who spends all of his money on luxurious living, services from sex workers, and gambling—the character's life ultimately ends in Bethlem Royal Hospital.[10]

However, his work was only tangentially politicized and was primarily regarded on its artistic merits. George Townshend, 1st Marquess Townshend produced some of the first overtly political cartoons and caricatures in the 1750s.[8][11]

Development

[edit]

The medium began to develop in England in the latter part of the 18th century—especially around the time of the French Revolution—under the direction of its great exponents, James Gillray and Thomas Rowlandson, both from London. Gillray explored the use of the medium for lampooning and caricature, and has been referred to as the father of the political cartoon.[3] Calling the king, prime ministers and generals to account, many of Gillray's satires were directed against George III, depicting him as a pretentious buffoon, while the bulk of his work was dedicated to ridiculing the ambitions of Revolutionary France and Napoleon.[3] The times in which Gillray lived were peculiarly favourable to the growth of a great school of caricature. Party warfare was carried on with great vigour and not a little bitterness; and personalities were freely indulged in on both sides. Gillray's incomparable wit and humour, knowledge of life, fertility of resource, keen sense of the ludicrous, and beauty of execution, at once gave him the first place among caricaturists.[13]

George Cruikshank became the leading cartoonist in the period following Gillray (1820s–40s). His early career was renowned for his social caricatures of English life for popular publications. He gained notoriety with his political prints that attacked the royal family and leading politicians and was bribed in 1820 "not to caricature His Majesty" (George IV) "in any immoral situation". His work included a personification of England named John Bull who was developed from about 1790 in conjunction with other British satirical artists such as Gillray and Rowlandson.[14]

Cartoonist's magazines

[edit]

The art of the editorial cartoon was further developed with the publication of the British periodical Punch in 1841, founded by Henry Mayhew and engraver Ebenezer Landells (an earlier magazine that published cartoons was Monthly Sheet of Caricatures, printed from 1830 and an important influence on Punch).[15] It was bought by Bradbury and Evans in 1842, who capitalised on newly evolving mass printing technologies to turn the magazine into a preeminent national institution. The term "cartoon" to refer to comic drawings was coined by the magazine in 1843; the Houses of Parliament were to be decorated with murals, and "carttons" for the mural were displayed for the public; the term "cartoon" then meant a finished preliminary sketch on a large piece of cardboard, or cartone in Italian. Punch humorously appropriated the term to refer to its political cartoons, and the popularity of the Punch cartoons led to the term's widespread use.[4]

Artists who published in Punch during the 1840s and 50s included John Leech, Richard Doyle, John Tenniel and Charles Keene. This group became known as "The Punch Brotherhood", which also included Charles Dickens who joined Bradbury and Evans after leaving Chapman and Hall in 1843. Punch authors and artists also contributed to another Bradbury and Evans literary magazine called Once A Week (est.1859), created in response to Dickens' departure from Household Words.[citation needed]

The most prolific and influential cartoonist of the 1850s and 60s was John Tenniel, chief cartoon artist for Punch, who perfected the art of physical caricature and representation to a point that has changed little up to the present day. For over five decades he was a steadfast social witness to the sweeping national changes that occurred during this period alongside his fellow cartoonist John Leech. The magazine loyally captured the general public mood; in 1857, following the Indian Rebellion and the public outrage that followed, Punch published vengeful illustrations such as Tenniel's Justice and The British Lion's Vengeance on the Bengal Tiger.[citation needed]

Maturation

[edit]

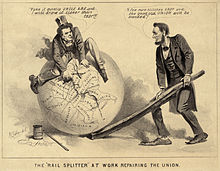

By the mid-19th century, major political newspapers in many countries featured cartoons designed to express the publisher's opinion on the politics of the day. One of the most successful was Thomas Nast in New York City, who imported realistic German drawing techniques to major political issues in the era of the Civil War and Reconstruction. Nast was most famous for his 160 editorial cartoons attacking the criminal characteristics of Boss Tweed's political machine in New York City. American art historian Albert Boime argues that:

As a political cartoonist, Thomas Nast wielded more influence than any other artist of the 19th century. He not only enthralled a vast audience with boldness and wit, but swayed it time and again to his personal position on the strength of his visual imagination. Both Lincoln and Grant acknowledged his effectiveness in their behalf, and as a crusading civil reformer he helped destroy the corrupt Tweed Ring that swindled New York City of millions of dollars. Indeed, his impact on American public life was formidable enough to profoundly affect the outcome of every presidential election during the period 1864 to 1884.[16]

Notable editorial cartoons include Benjamin Franklin's Join, or Die (1754), on the need for unity in the American colonies; The Thinkers Club (1819), a response to the surveillance and censorship of universities in Germany under the Carlsbad Decrees; and E. H. Shepard's The Goose-Step (1936), on the rearmament of Germany under Adolf Hitler. The Goose-Step is one of a number of notable cartoons first published in the British Punch magazine.[citation needed]

Recognition

[edit]Institutions which archive and document editorial cartoons include the Center for the Study of Political Graphics in the United States,[17] and the British Cartoon Archive in the United Kingdom.[18]

Editorial cartoons and editorial cartoonists are recognised by a number of awards, for example the Pulitzer Prize for Editorial Cartooning (for US cartoonists, since 1922) and the British Press Awards' "Cartoonist of the Year".[citation needed]

Modern political cartoons

[edit]Political cartoons can usually be found on the editorial page of many newspapers, although a few (such as Garry Trudeau's Doonesbury) are sometimes placed on the regular comic strip page. Most cartoonists use visual metaphors and caricatures to address complicated political situations, and thus sum up a current event with a humorous or emotional picture.[citation needed]

Yaakov Kirschen, creator of the Israeli comic strip Dry Bones, says his cartoons are designed to make people laugh, which makes them drop their guard and see things the way he does. In an interview, he defined his objective as a cartoonist as an attempt to "seduce rather than to offend."[19]

Modern political cartooning can be built around traditional visual metaphors and symbols such as Uncle Sam, the Democratic donkey and the Republican elephant. One alternative approach is to emphasize the text or the story line, as seen in Doonesbury which tells a linear story in comic strip format.[citation needed]

Cartoons have a great potential to political communication capable of enhancing political comprehension and reconceptualization of events, through specific frames of understanding. Mateus' analysis "seems to indicate that the double standard thesis can be actually applied to trans-national contexts. This means that the framing of politics and business may not be limited to one country but may reflect a political world-view occurring in contemporary societies. From the double standard standpoint, there are no fundamental differences in the way Canadian political cartoonists and Portuguese political cartoons assess politics and business life". The paper does not tell that all political cartoons are based on this kind of double standard, but suggests that the double standard thesis in Political Cartoons may be a frequent frame among possible others.[20]

A political cartoon commonly draws on two unrelated events and brings them together incongruously for humorous effect. The humour can reduce people's political anger and so serves a useful purpose. Such a cartoon also reflects real life and politics, where a deal is often done on unrelated proposals beyond public scrutiny.[citation needed]

Pocket cartoons

[edit]A pocket cartoon is a form of cartoon which generally consists of a topical political gag/joke and appears as a single-panel single-column drawing. It was introduced by Osbert Lancaster in 1939 at the Daily Express.[21] A 2005 obituary by The Guardian of its pocket cartoonist David Austin said "Newspaper readers instinctively look to the pocket cartoon to reassure them that the disasters and afflictions besetting them each morning are not final. By taking a sideways look at the news and bringing out the absurd in it, the pocket cartoonist provides, if not exactly a silver lining, then at least a ray of hope."[22]

Controversies related to cartoons

[edit]Editorial cartoons sometimes cause controversies.[23] Examples include the Jyllands-Posten Muhammad cartoons controversy and Charlie Hebdo shooting (stemming from the publication of cartoons related to Islam) and the 2007 Bangladesh cartoon controversy.[citation needed]

Libel lawsuits have been rare. In Britain, the first successful lawsuit against a cartoonist in over a century came in 1921 when J.H. Thomas, the leader of the National Union of Railwaymen (NUR), initiated libel proceedings against the magazine of the British Communist Party. Thomas claimed defamation in the form of cartoons and words depicting the events of "Black Friday"—when he allegedly betrayed the locked-out Miners' Federation. Thomas won his lawsuit, and restored his reputation.[24]

See also

[edit] Cartoon portal

Cartoon portal- Attitude: The New Subversive Cartoonists

- Comics journalism

- Gag cartoon

- Humor comics

- List of editorial cartoonists

References

[edit]- ^ Sterling, Christopher (2009). Encyclopedia of Journalism. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc. pp. 253–261. ISBN 978-0-7619-2957-4.

- ^ Shelton, Mitchell. "Editorial Cartoons: An Introduction | HTI". hti.osu.edu. Retrieved 13 March 2024.

- ^ a b c "Satire, sewers and statesmen: why James Gillray was king of the cartoon". The Guardian. 16 June 2015.

- ^ a b Appelbaum & Kelly 1981, p. 15.

- ^ J. B. Nichols, 1833 p. 192 "PLATE VIII. ... Britannia 1763"

- ^ J. B. Nichols, 1833 p. 193 "Retouched by the Author, 1763"

- ^ Richetti, John J. (2005). The Cambridge history of English literature, 1660–1780. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-78144-2., p. 85.

- ^ a b Charles Press (1981). The Political Cartoon. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. p. 34. ISBN 9780838619018.

- ^ See Ronald Paulson, Hogarth's Graphic Works (3rd edition, London 1989), no. 43.

- ^ "A Rake's Progress". Sir John Soane's Museum. 2012. Retrieved 13 December 2013.

- ^ Chris Upton. "Birth of England's pocket cartoon". Birmingham Post & Mail – via The Free Library.

- ^ Martin Rowson, speaking on The Secret of Drawing, presented by Andrew Graham Dixon, BBCTV

- ^ "James Gillray: The Scourge of Napoleon". HistoryToday.

- ^ Gatrell, Vic. City of Laughter: Sex and Satire in Eighteenth-Century London. New York: Walker & Co., 2006

- ^ "Caricature and cartoon". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Albert Boime, "Thomas Nast and French Art", American Art Journal (1972) 4#1 pp. 43–65

- ^ "Collection | political-graphics". CSPG. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ "British Cartoon Archive at University of Kent". Culture24. Archived from the original on 11 March 2020. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Davis, Barry (31 May 2011). "'Dry Bones': Row shows clash of civilizations, Jerusalem Post". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 16 May 2014.

- ^ Mateus, Samuel; University, Madeira (2016). "Political Cartoons as communicative weapons – the hypothesis of the "Double Standard Thesis" in three Portuguese cartoons". Estudos em Comunicação (23): 195–221. doi:10.20287/ec.n23.a09. hdl:10400.13/2921. ISSN 1646-4974.

- ^ David Smith, The Observer, 23 November 2008, Timeless appeal of the classic joke

- ^ Nicola Jennings and Patrick Barkham, The Guardian, 21 November 2005, David Austin: Guardian pocket cartoonist with a sceptically humanist view of the news

- ^ Navasky, Victor S. (12 November 2011). "Why Are Political Cartoons Incendiary?". The New York Times.

- ^ Samuel S. Hyde, "'Please, Sir, he called me "Jimmy!' Political Cartooning before the Law: 'Black Friday,' J.H. Thomas, and the Communist Libel Trial of 1921", Contemporary British History (2011) 25#4 pp 521–550

Further reading

[edit]- Adler, John, and Hill, Draper. Doomed by Cartoon: How Cartoonist Thomas Nast and the New York Times Brought Down Boss Tweed and His Ring of Thieves (2008).

- Gocek, Fatma Muge. Political Cartoons in the Middle East: Cultural Representations in the Middle East (Princeton series on the Middle East) (1998)

- Heitzmann, William Ray. "The political cartoon as a teaching device". Teaching Political Science 6.2 (1979): 166–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/00922013.1979.11000158

- Hess, Stephen, and Sandy Northrop. American Political Cartoons, 1754–2010: The Evolution of a National Identity (2010)

- Keller, Morton. The Art and Politics of Thomas Nast (1975).

- Knieper, Thomas. "Caricature and cartoon". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Krauss, Jerelle. All the Art That's Fit to Print (And Some That Wasn't): Inside The New York Times Op-Ed Page (2009). excerpt ISBN 978-0-231-13825-3

- "It's No Laughing Matter". Classroom Materials: Presentations and Activities. Library of Congress.

- McCarthy, Michael P. "Political Cartoons in the History Classroom." History Teacher 11.1 (1977): 29–38. online

- McKenna, Kevin J. All the Views Fit to Print: Changing Images of the U.S. in 'Pravda' Political Cartoons, 1917–1991 (2001).

- Mateus, Samuel. ""Political Cartoons as communicative weapons – the hypothesis of the 'Double Standard Thesis' in three Portuguese cartoons", Communication Studies, nº23, pp. 195–221 (2016).

- Morris, Frankie. Artist of Wonderland: The Life, Political Cartoons, and Illustrations of Tenniel (Victorian Literature and Culture Series) (2005)

- Navasky, Victor S. (2013). The Art of Controversy: Political Cartoons and Their Enduring Power. Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0307957207.

- Nevins, Allan. A Century of Political Cartoons: Caricature in the United States from 1800 to 1900 (1944).

- Press, Charles. The Political Cartoon (1981).

- Scully, Richard. Eminent Victorian Cartoonists, 3 vols. London: Political Cartoon Society (2018).

External links

[edit]- History of Cartoon History of Cartoon from Toons Mag

- American Association of Editorial Cartoonists Political cartoons by the members of the American Association of Editorial Cartoonists

- TED Talk: The power of cartoons

- About.com: Political Cartoons Archived 28 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine Comprehensive guide to political editorial cartoons on the Web

- Globe Cartoon: archived editorial cartoons, searchable by themes and keywords

- Using editorial cartoons in the classroom Sources, analysis, interpretation (mostly English with some German)

- Gettysburg College Civil War Era Digital Collection Contains over 300 Civil War Era political cartoons

- The Role of Puck's Cartoons in Gilded Age Politics from American Studies at the University of Virginia

- CartoonMovement.com: Political Cartoons and Comics Journalism from around the world

- "Cartoons in American History" guide to websites

- John Tinney McCutcheon Editorial Cartoon Collection at the University of Missouri

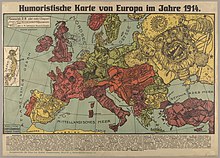

- Caricature Maps of World War I Archived 11 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine by Gayle Olson-Raymer